Aspirin: A New Hope in Fighting Pancreatic Cancer

Table of contents

Commonly used to treat headachesaspirinAspirin has now been discovered by scientists to potentially help defend against one of the deadliest cancers.pancreatic cancer?

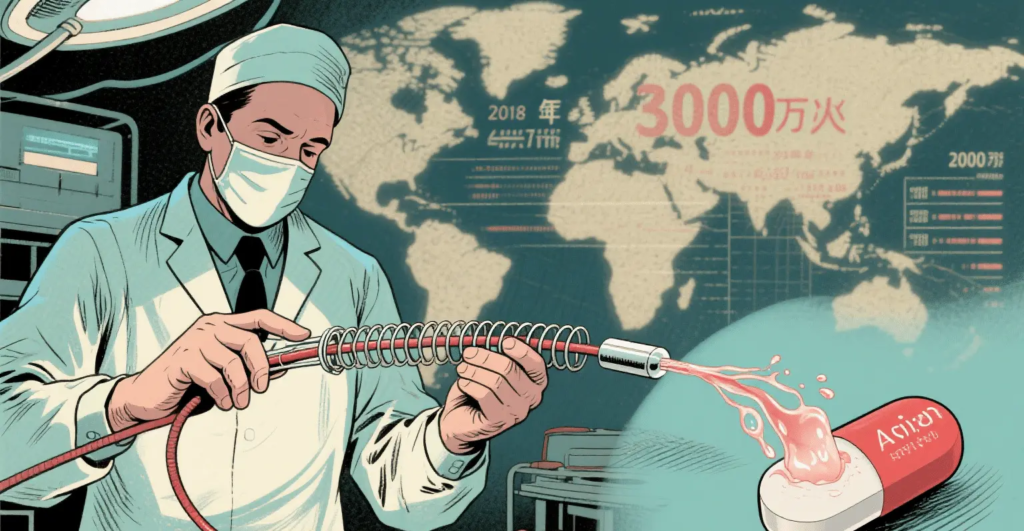

The findings were published in the medical journal *Gut* in 2025. This study analyzed data from over 120,000 diabetic patients and found that long-term use...aspirinIt was associated with a 42% reduction in pancreatic cancer risk, a 57% reduction in cancer-related mortality, and a 22% reduction in overall mortality. This groundbreaking discovery not only reveals the multiple pharmacological potentials of aspirin but also provides new directions for pancreatic cancer prevention strategies.

| Evaluation indicators | Risk changes | Correlation strength |

|---|---|---|

| Risk of developing pancreatic cancer | reduce | 42% |

| Cancer-related mortality | decline | 57% |

| Overall mortality rate | reduce | 22% |

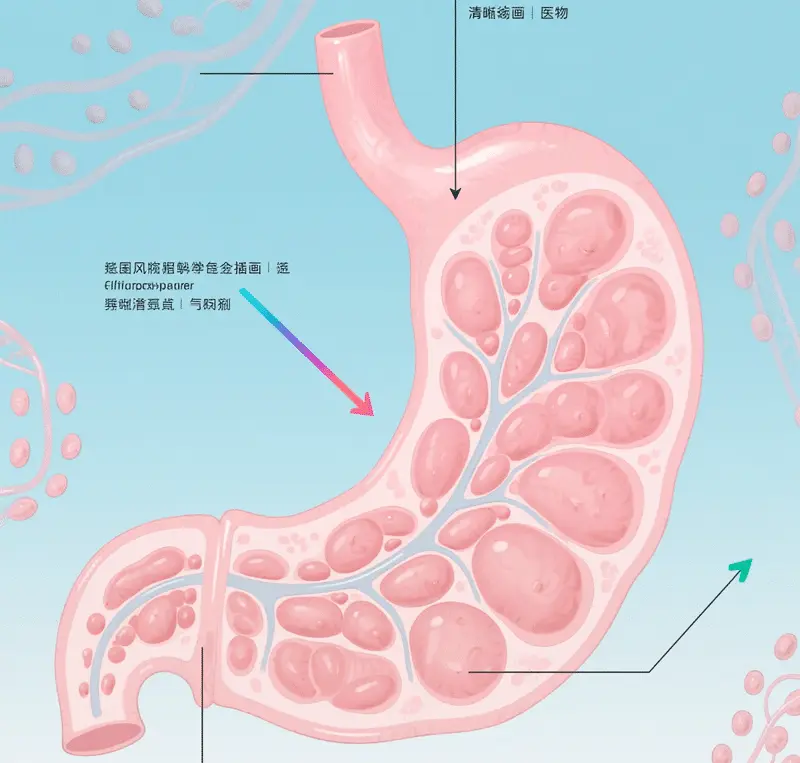

Pancreatic cancer is known as the "silent killer" because its early symptoms are often subtle, and most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, with a five-year survival rate of only about 101 TP3T. Meanwhile, the link between diabetes and pancreatic cancer is receiving increasing attention. High blood sugar and insulin imbalances can lead to abnormal proliferation of pancreatic cells, increasing the risk of cancer. Even more alarming is that approximately 601 TP3T pancreatic cancer patients were diagnosed with diabetes within a year before their cancer diagnosis, making new-onset diabetes an early warning sign of pancreatic cancer. Aspirin, as an inexpensive and long-established drug, would have significant public health implications if it could play a role in cancer prevention.

What is aspirin?

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) is also known as...Acetyl salicylic acidby product nameaspirinAspirin, a well-known salicylic acid derivative, is commonly used as a pain reliever, fever reducer, and anti-inflammatory. Its historical roots date back thousands of years, when ancient civilizations discovered the medicinal value of willow-like plants. Archaeological evidence shows that as early as 3000 BC, the Sumerians recorded methods of using willow leaves to treat pain on clay tablets. The oldest medical document from ancient Egypt, the Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BC), also details how willow bark preparations were used to relieve arthritis pain and reduce inflammation.

A pain-relieving secret recipe from willow bark

Hippocrates, the father of ancient Greek medicine, suggested in the 5th century BC that drinking tea made from willow leaves could alleviate childbirth pain and treat fever. Similarly, the ancient Chinese medical classic, the *Huangdi Neijing*, records the heat-clearing and detoxifying properties of willow branches. These medical practices scattered throughout various ancient civilizations demonstrate that the medicinal value of willow trees was independently discovered and widely applied—a common knowledge.

However, these ancient remedies had significant limitations: willow bark extract was extremely bitter, highly irritating to the stomach, and its efficacy was inconsistent. These drawbacks prompted scientists to search for more effective and safer alternatives, paving the way for the development of aspirin.

Scientific breakthroughs and their emergence (19th century)

Isolation and purification of active ingredients

In the mid-to-late 18th century, scientific research into the medicinal value of willow entered a new phase. In 1763, the British clergyman Edward Stone submitted a detailed report to the Royal Society, recording his successful use of willow bark powder to treat symptoms of malaria fever. This was the first scientific record of the therapeutic effects of willow in modern times.

In 1828, Johann Andreas Büchner, professor of pharmacology at the University of Munich, successfully isolated the active ingredient, a yellow crystal, from willow bark, naming it "salicin." This breakthrough laid the foundation for subsequent research. In 1829, French chemist Henri Leroux further purified salicin. In 1838, Italian chemist Raphael Piria synthesized salicylic acid based on salicin, a crucial step towards aspirin.

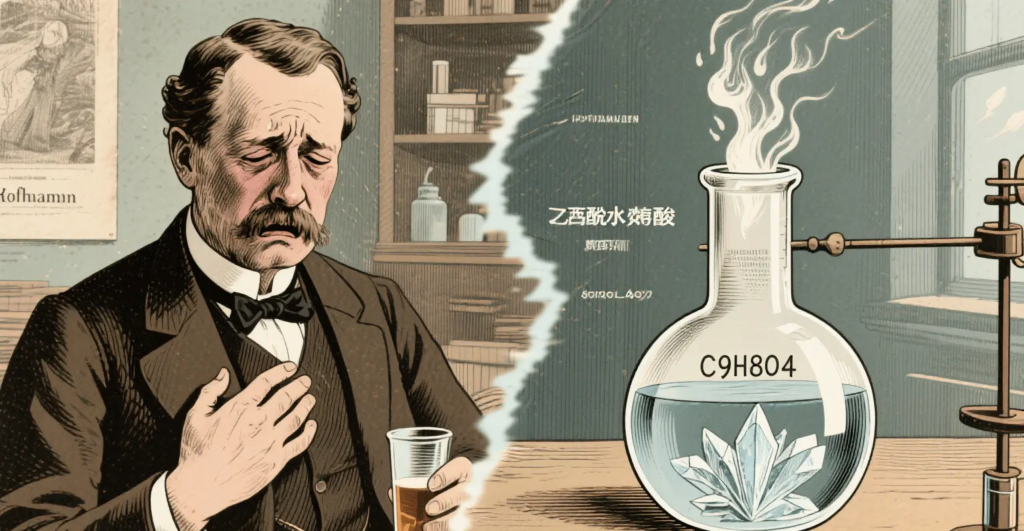

However,salicylic acidA serious problem existed: it was extremely irritating to the stomach and had an unbearable taste, leading many patients to endure the pain rather than take the drug. The task of solving this problem fell to the German chemist Felix Hoffmann.

Hoffmann's historic breakthrough

In 1897, in GermanyBayerA young chemist named Felix Hoffmann was given a special task: to find a milder salicylic acid derivative for his father, who suffered from rheumatism. Hoffmann successfully introduced an acetyl group into the salicylic acid molecule using an acetylation reaction, synthesizing acetylsalicylic acid—which is what we know today as aspirin.

Hoffmann's discovery was not entirely original; French chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt had synthesized acetylsalicylic acid in 1853 but failed to recognize its medicinal value. Hoffmann's key contribution lay in developing a feasible method for large-scale production and leveraging Bayer's resources to bring it to market.

Bayer quickly recognized the commercial value of this discovery and commissioned pharmacologist Heinrich Dresser to conduct a clinical evaluation. Dresser's test results were encouraging: acetylsalicylic acid not only retained the analgesic and antipyretic properties of salicylic acid but also significantly reduced its irritation to the stomach. In 1899, Bayer began mass production of the drug under the brand name "Aspirin," where "A" stands for acetyl, "spir" comes from the plant source of salicylic acid, Spiraea ulmaria, and the suffix "in" was a common ending for drugs at the time.

The table below shows the key events in the development of aspirin:

| Time | Development history |

|---|---|

| 1500 BC | The ancient Egyptian papyrus records the use of willow leaves to treat fever. |

| 4th century BC | The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates mentioned that chewing willow bark could relieve childbirth pain and reduce fever. |

| middle Ages | Arab doctors used willow bark to treat pain and fever. |

| 1763 | British clergyman Edward Stone reported to the Royal Society on the antipyretic properties of willow bark. |

| 1828 | German pharmacist Johann Buchner extracted willow bark from willow bark. |

| 1838 | Italian chemist Raphael Piria converted salicylates into salicylic acid. |

| 1853 | French chemist Charles Frédéric Gérard synthesized acetylsalicylic acid, but it did not attract much attention. |

| 1897 | Felix Hoffmann successfully synthesized acetylsalicylic acid at Bayer. |

| 1899 | Bayer patented acetylsalicylic acid, named it aspirin, and launched it on the market. |

| 1950s | The US FDA has approved aspirin for the treatment of colds and flu in children. |

| 1960s-1970s | John Wen discovered the mechanism by which aspirin inhibits prostaglandin synthesis. |

| Since the 1980s | Aspirin was found to have antiplatelet aggregation effects and is used for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. |

| In recent years | Research on the preventive effects of aspirin on certain cancers |

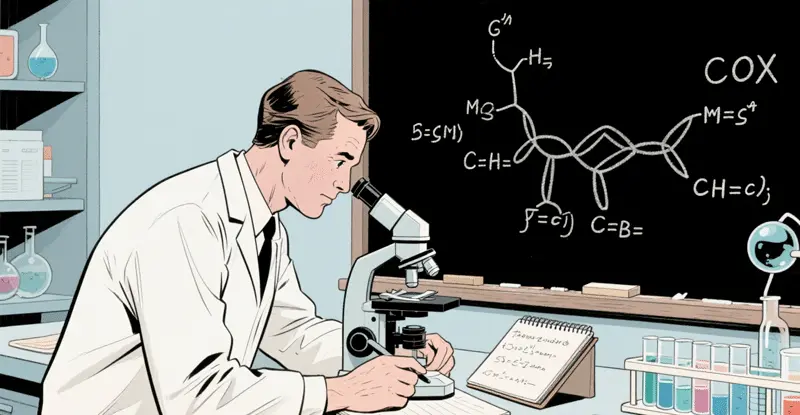

Mechanisms of action for antipyresis, analgesia and anti-inflammation

Aspirin's antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects are primarily achieved by inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX). COX has two isoenzymes: COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is continuously expressed under normal physiological conditions and participates in physiological functions such as maintaining the integrity of the gastrointestinal mucosa, regulating renal blood flow, and platelet aggregation. COX-2 is normally expressed at very low levels, but under inflammatory stimuli, such as bacterial or viral infections or tissue damage, it can be induced to be expressed in large quantities, catalyzing the conversion of arachidonic acid into inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins (PGs) and prostacyclin (PGIs).

Aspirin irreversibly acetylates serine residues at the active site of COX, inactivating COX and thus inhibiting the synthesis of PG and PGI. PG has pyrogenic, analgesic, and inflammatory-enhancing effects, while PGI has vasodilatory and antiplatelet aggregation effects. By inhibiting the synthesis of PG and PGI, aspirin can lower the body temperature set point of the thermoregulatory center, thus reducing body temperature in febrile patients; reduce the sensitivity of pain receptors to painful stimuli, achieving an analgesic effect; and inhibit vasodilation and exudation at inflamed sites, thereby exerting an anti-inflammatory effect.

Rapid expansion and diversification of applications (first half of the 20th century)

Global reach and brand establishment

In the early 20th century, aspirin experienced explosive growth. Bayer employed an innovative marketing strategy, distributing free samples and scientific papers to doctors to demonstrate aspirin's efficacy and safety. This "scientific marketing" approach greatly promoted the medical community's acceptance of the new drug.

In 1915, Bayer achieved another key breakthrough—producing aspirin in tablet form instead of the previous powder. This improvement greatly enhanced the convenience of administration and dosage accuracy, making aspirin the first synthetic drug in the modern sense.

The two World Wars had a complex impact on the global spread of aspirin. During World War I, Bayer, a German company, had its patents confiscated in Allied markets, and the name aspirin became the generic name in many countries, leading to the production of the drug by several companies. Although Bayer lost its patent protection, this actually accelerated the global adoption of aspirin.

By 1950, aspirin had become the world's best-selling painkiller, found in the medicine cabinets of almost every household in Western countries. In 1950, aspirin was recognized by the Guinness World Records as the "best-selling painkiller," a position it held for more than half a century.

Preliminary Unveiling of the Mystery of its Mechanism

Despite its proven efficacy, aspirin's mechanism of action remained incompletely understood by scientists until the mid-20th century. In 1971, British pharmacologist John Vane and his team published a landmark study revealing that aspirin exerts its analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic effects by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. Prostaglandins are important chemical mediators in the body, involved in pain, inflammation, and fever processes.

This discovery not only explained the pharmacological effects of aspirin but also pioneered the field of research on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Van Ein's work, along with other research, earned him the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, highlighting aspirin's central role in medical science.

An unexpected discovery of its cardiovascular protective effects

In the latter half of the 20th century, aspirin underwent its most significant role transformation—from a simple painkiller to a cardiovascular disease prevention drug. This transformation began with an unexpected observation.

In 1948, American physician Lawrence Craven noticed an increased risk of bleeding in children who chewed aspirin gum after undergoing tonsillectomy. He speculated that aspirin might have an anticoagulant effect. Further research revealed that adults who regularly took aspirin had a significantly lower rate of heart attacks. In 1950, he suggested using aspirin as a preventative medicine for cardiovascular disease, but this view was not widely accepted by the medical community at the time.

In 1974, the first randomized controlled trial led by Canadian physician Henry Barnett confirmed the effectiveness of aspirin in preventing stroke. In the 1980s, the landmark Physicians' Health Study clearly showed that taking 325 mg of aspirin every other day could reduce the risk of myocardial infarction by 441 TP3T.

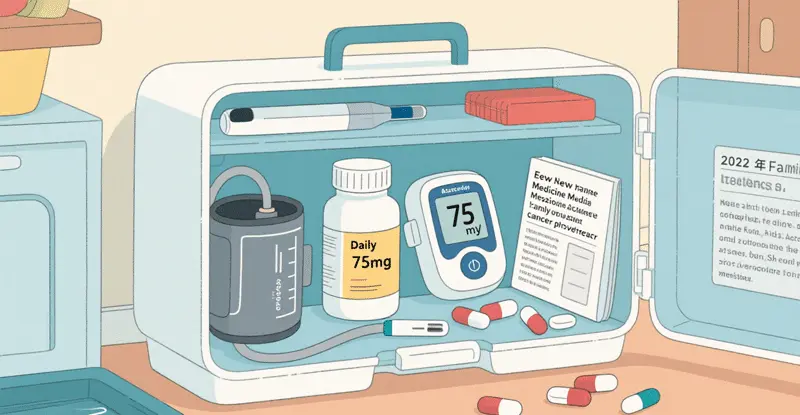

These studies revolutionized the use of aspirin. By the 1990s, low-dose aspirin (usually 75-100 mg/day) had become the standard preventative medication for high-risk groups of cardiovascular disease.

Mechanism of action against platelet aggregation

Platelets play a crucial role in thrombosis. Upon activation, platelets release a series of mediators, such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2), which can further activate other platelets, leading to platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. TXA2 is a potent platelet aggregation inducer and vasoconstrictor, catalyzed by COX-1 in platelets to produce arachidonic acid.

Aspirin irreversibly inhibits COX-1 activity in platelets and prevents the synthesis of TXA2, thereby inhibiting platelet aggregation. Since platelets lack a nucleus and cannot resynthesize COX-1, the inhibitory effect of aspirin on platelets is permanent. After a single dose of aspirin, its inhibitory effect on platelets can last for 7–10 days until new platelets are generated. Low doses of aspirin (75–150 mg/day) primarily inhibit COX-1 in platelets, with less effect on COX-2 in vascular endothelial cells. Vascular endothelial cells can continuously synthesize PGI2, which has anti-platelet aggregation and vasodilatory effects, thus inhibiting platelet aggregation without significantly increasing the risk of bleeding.

Preliminary exploration of anti-cancer potential

Around the same time, researchers began to focus on the potential anti-cancer properties of aspirin. In 1988, Australian researchers found that people who regularly took aspirin had a lower incidence of colon cancer. Subsequent epidemiological studies supported this finding, indicating that long-term, regular use of aspirin can reduce the risk of various cancers, especially digestive tract cancers.

A major study published in The Lancet in 2012 showed that daily aspirin use for more than three years can reduce the incidence of various cancers by approximately 251 TP3T and the mortality rate by 151 TP3T. These findings have opened up new frontiers in the application of aspirin, although further research is still needed on specific regimens for its use as a routine anti-cancer prevention measure.

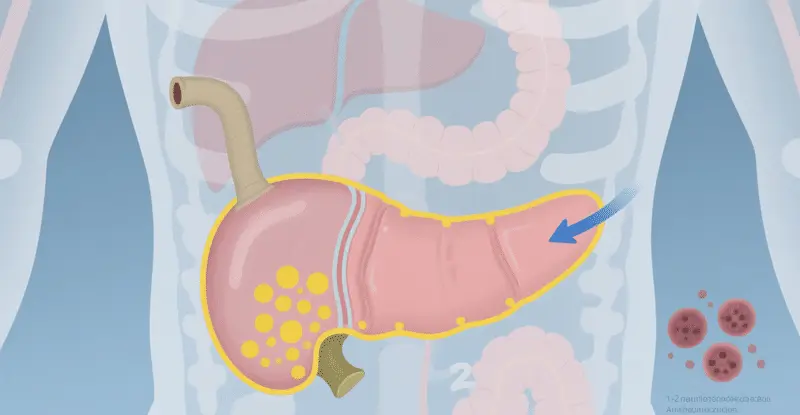

Aspirin and Pancreatic Cancer Prevention: Background and Key Findings

This study, based on large-scale epidemiological data, followed 120,000 diabetic patients for 10 years. The results showed that the group regularly taking low-dose aspirin (typically 75-100 mg daily) had a significantly lower incidence of pancreatic cancer than the group that did not. Specific data are as follows:

- Reduced risk of pancreatic cancer by 42%The incidence rate in the treatment group was 0.12%, while it was 0.21% in the non-treatment group.

- Cancer-related mortality decreased by 571 TP3TThe cancer mortality risk was 0.05% in the treatment group and 0.12% in the non-treatment group.

- Overall mortality rate decreased by 22%The overall mortality rate was 1.81 TP3T in the treatment group and 2.31 TP3T in the non-treatment group.

These data were not only statistically significant, but also remained robust after multivariate adjustment (e.g., age, sex, blood glucose control). The study further indicated that the protective effect of aspirin was more pronounced in long-term users (over 5 years), suggesting that its effects may accumulate over time.

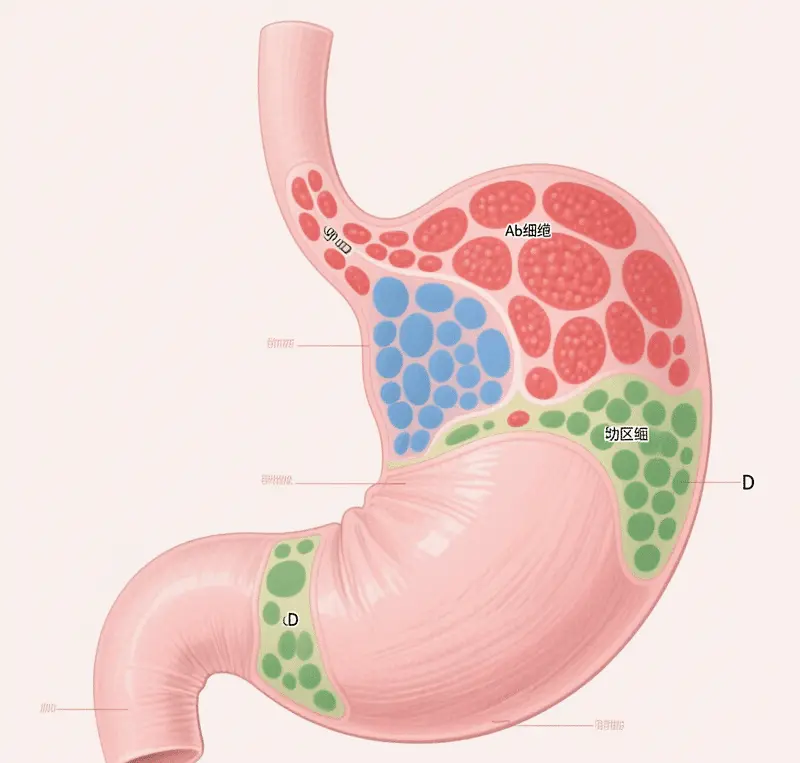

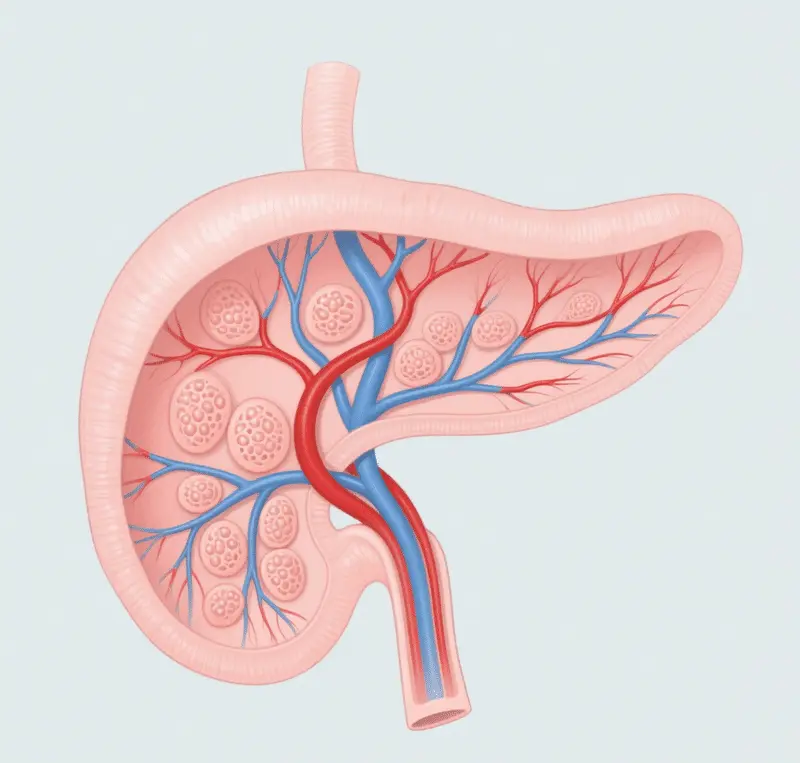

The link between diabetes and pancreatic cancer: Why focus on this group?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and pancreatic cancer forms a crucial basis for this study. On one hand, diabetes is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer—hyperglycemia and insulin resistance may promote inflammation and cell proliferation, thereby inducing carcinogenesis. On the other hand, pancreatic cancer itself can lead to secondary diabetes because the tumor destroys insulin-secreting cells. Statistics show that approximately 25-50% pancreatic cancer patients also have diabetes, and about 60% cases of newly diagnosed diabetes develop within one year prior to cancer diagnosis.

This association makes diabetic patients a key population for pancreatic cancer prevention. Aspirin, as an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agent, may block this process through multiple mechanisms.

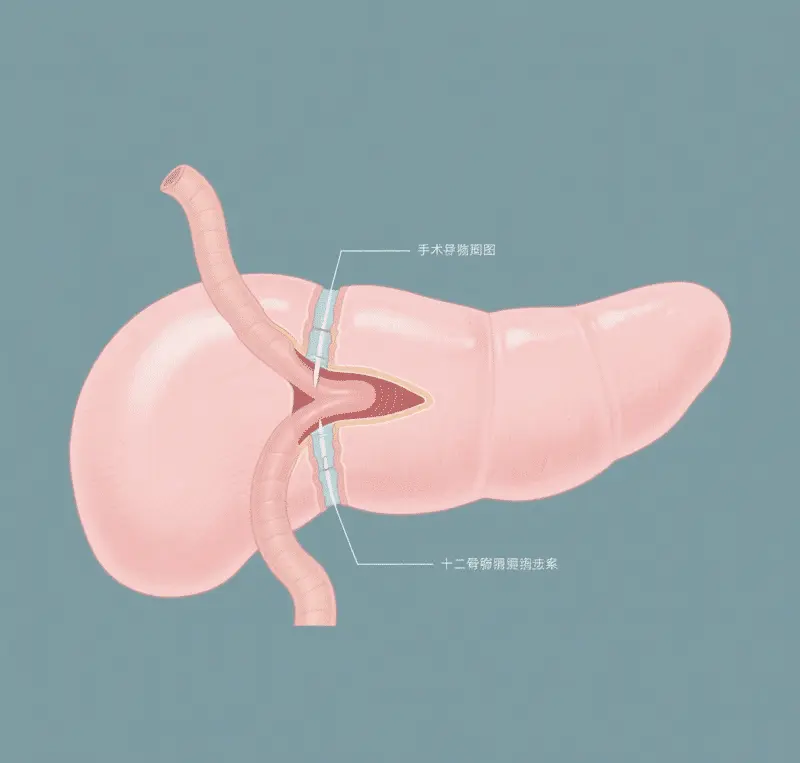

Mechanism of action of aspirin: three key pathways

- Anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic

Chronic inflammation is a common driver of cancer. In pancreatic cancer, inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α and IL-6) promote the formation of the tumor microenvironment. Aspirin reduces inflammation levels by inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2) and reducing the production of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins. Simultaneously, it inhibits the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), blocking tumor angiogenesis, cutting off the "food supply" to cancer cells, and limiting their growth and spread. - Regulating cell homeostasis and promoting apoptosis

Aspirin activates a range of intracellular signaling pathways, such as the AMPK and p53 pathways, regulating the cell cycle and energy metabolism. In pancreatic cells, it induces programmed cell death (apoptosis) in damaged cells, rather than leading to cancer through cumulative mutations. Furthermore, aspirin may also inhibit the activity of oncogenes through epigenetic regulation, such as DNA methylation. - Enhanced immune surveillance

Tumor cells often evade recognition by the immune system through "camouflage." Aspirin has been found to activate T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, enhancing the immune system's ability to detect and eliminate cancer cells. This mechanism is particularly important in pancreatic cancer, as the pancreatic tumor microenvironment is typically highly immunosuppressive.

These mechanisms work together to make aspirin a multi-target preventative agent. However, it is worth noting that its effectiveness may vary depending on individual genetic background, lifestyle, and medication history.

Recommendations and precautions for using aspirin

Despite its promising future, aspirin is not a panacea. Its main risks include gastrointestinal bleeding and cerebral hemorrhage, especially for long-term users. The following groups should use it with caution or avoid self-medication:

- People currently taking anticoagulants (such as warfarin)

- People allergic to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Patients with severe liver and kidney dysfunction

- Children and adolescentsAs mentioned above, aspirin should not be used in children and adolescents during viral infections to prevent Reye's syndrome.

- People allergic to aspirin or other salicylatesAspirin should not be used to avoid severe allergic reactions.

- Patients with bleeding tendenciesIn conditions such as hemophilia and thrombocytopenic purpura, aspirin can worsen bleeding tendencies and should be avoided.

- Patients with active peptic ulcersAspirin may cause ulcer bleeding or perforation, worsening the condition; therefore, it is contraindicated in patients with active peptic ulcers.

- Patients with severe liver and kidney dysfunctionAspirin can further damage liver and kidney function, therefore it is not suitable for patients with severe liver or kidney dysfunction.

- Pregnant women and breastfeeding womenAspirin use by pregnant women, especially in late pregnancy, may increase the risk of fetal bleeding, leading to neonatal hemorrhage. Aspirin used by breastfeeding women can also have adverse effects on infants through breast milk secretion. Therefore, pregnant and breastfeeding women should use aspirin with caution or avoid using it altogether.

side effect

- Gastrointestinal reactionsThese are the most common side effects of aspirin, including nausea, vomiting, upper abdominal discomfort or pain, etc. Long-term or high-dose use can cause gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers. The mechanism is mainly that aspirin inhibits the activity of COX-1 in the gastrointestinal mucosa, reduces the synthesis of PG, which has a protective effect on the gastric mucosa, and leads to damage to the gastric mucosal barrier function.

- Bleeding tendencyBecause aspirin inhibits platelet aggregation, it can prolong bleeding time and increase the risk of bleeding. In severe cases, it can cause nosebleeds, gum bleeding, skin ecchymosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage.

- Liver and kidney dysfunctionHigh doses of aspirin can cause liver and kidney damage, manifesting as elevated liver enzymes and abnormal kidney function. However, this damage is usually reversible and can be reversed after discontinuation of the drug.

- Allergic reactionsA small number of patients may experience allergic reactions, manifesting as asthma, urticaria, angioedema, or shock. Aspirin-induced asthma is particularly unique, occurring more frequently in asthma patients. Taking aspirin can rapidly trigger an asthma attack, which in severe cases can be life-threatening.

- Central nervous system responseA small number of patients may experience reversible tinnitus, hearing loss, and other central nervous system symptoms after taking aspirin, which usually occur after the blood drug concentration reaches a certain level (200-300 μg/L).

- Reye's syndromeTaking aspirin during viral infections (such as influenza, chickenpox, etc.) in children and adolescents may induce Reye's syndrome, a rare but serious disease characterized by acute encephalopathy and hepatic steatosis, which can lead to death or permanent brain damage. Therefore, the use of aspirin in children and adolescents during viral infections is currently not recommended.

Other applications

In pediatrics, aspirin is used to treat Kawasaki disease. Kawasaki disease is an acute febrile rash-like pediatric illness characterized by systemic vasculitis. Aspirin can reduce the inflammatory response and prevent intravascular thrombosis. Furthermore, studies have shown that enteric-coated aspirin tablets used in the early to mid-pregnancy period (12-16 weeks) can help prevent preeclampsia, typically starting with 50-150 mg orally and continuing until 26-28 weeks. For obstetric patients with antiphospholipid syndrome planning pregnancy, a low-dose aspirin of 50-100 mg daily is recommended throughout the pregnancy. Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by thrombosis and pathological pregnancies (such as placenta previa, miscarriage, and gestational hypertension). However, these uses are not explicitly mentioned in the drug's instructions and should be used cautiously under the guidance of a physician.

Future Outlook: Precision Prevention and Personalized Medicine

Aspirin research represents a trend: a shift from "treating disease" to "preventing disease." In the future, scientists may be able to identify the groups most likely to benefit through biomarkers (such as inflammatory markers or gene mutations), achieving precision prevention. At the same time, the combination of aspirin with other therapies (such as immunotherapy) is also worth exploring.

However, challenges remain. Pancreatic cancer is highly heterogeneous, and different subtypes may respond differently to aspirin. Furthermore, the risk-benefit ratio of long-term use requires further validation through clinical trials. Currently, several international studies (such as the extended analysis of the ASPREE trial) are underway, and the results will provide stronger evidence for this field.

A list of common aspirin brands

| Brand Name (Chinese) | Brand Name (English) | Main dosage forms and common dosages | Main uses (based on instruction manuals/product information) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayer | Bayer | Enteric-coated tablets (100mg) | Prevention of myocardial infarction, prevention of thromboembolism, and transient ischemic attack. | Produced by the German pharmaceutical company Bayer, it is one of the more well-known aspirin brands. |

| Burke | Bokey | Enteric-coated capsules (100mg) | Prevention of myocardial infarction, prevention of thromboembolism, and transient ischemic attack. | |

| aspirin | – | Quick-acting tablets | – |

in conclusion

Aspirin's evolution from a simple headache remedy to a potential cancer preventative demonstrates the unpredictability and allure of scientific discovery. Research from the University of Hong Kong offers new hope to high-risk groups for pancreatic cancer (such as diabetic patients), but also reminds us that drug use must be based on scientific evidence and medical guidance. In the medical field, there are no "miracle drugs," only continuously deepening understanding and prudent application. The story of aspirin perfectly illustrates this principle.

Appendix: Data Charts

Figure 1: Comparison of pancreatic cancer risk between the aspirin-taking group and the non-aspirin-taking group.

(Data source: Gut 2025; Hong Kong University Study)

| Group | Pancreatic cancer incidence | Cancer-related mortality | Overall mortality rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin group | 0.12% | 0.05% | 1.8% |

| Group that did not take aspirin | 0.21% | 0.12% | 2.3% |

| Risk reduction rate | 42% | 57% | 22% |

Figure 2: Time-series association between diabetes and pancreatic cancer

Approximately 601 TP3T pancreatic cancer patients were diagnosed with diabetes within a year before their cancer diagnosis, suggesting that a new onset of diabetes may be an early sign of pancreatic cancer.

This article is based on existing scientific literature and is for educational reference only. It does not constitute medical advice. Please consult a professional physician before using any medication.

Data source: Gut 2025; TurboScribe.ai transcription reference removed for clarity.

Further reading:

![[有片]把與生俱來的「好色」,用以點燃事業的雄心](https://findgirl.org/storage/2025/11/有片把與生俱來的「好色」,用以點燃事業的雄心-300x225.webp)

-300x225.webp)